by Xiong Weisheng

In the heart of Silicon Valley, a counter-intuitive trend is taking root. Martin Casado, general partner at Andreessen Horowitz (a16z), recently estimated that 80 per cent of open-source artificial intelligence (AI) start-ups pitching to the firm are now building upon Chinese models. This represents a structural shift in the global AI economy.

From public sectors in Southeast Asia to enterprise developers in Latin America, the adoption of Chinese large language models (LLMs) is accelerating - driven less by ideological alignment than by a pragmatic calculation of cost, performance, and digital sovereignty.

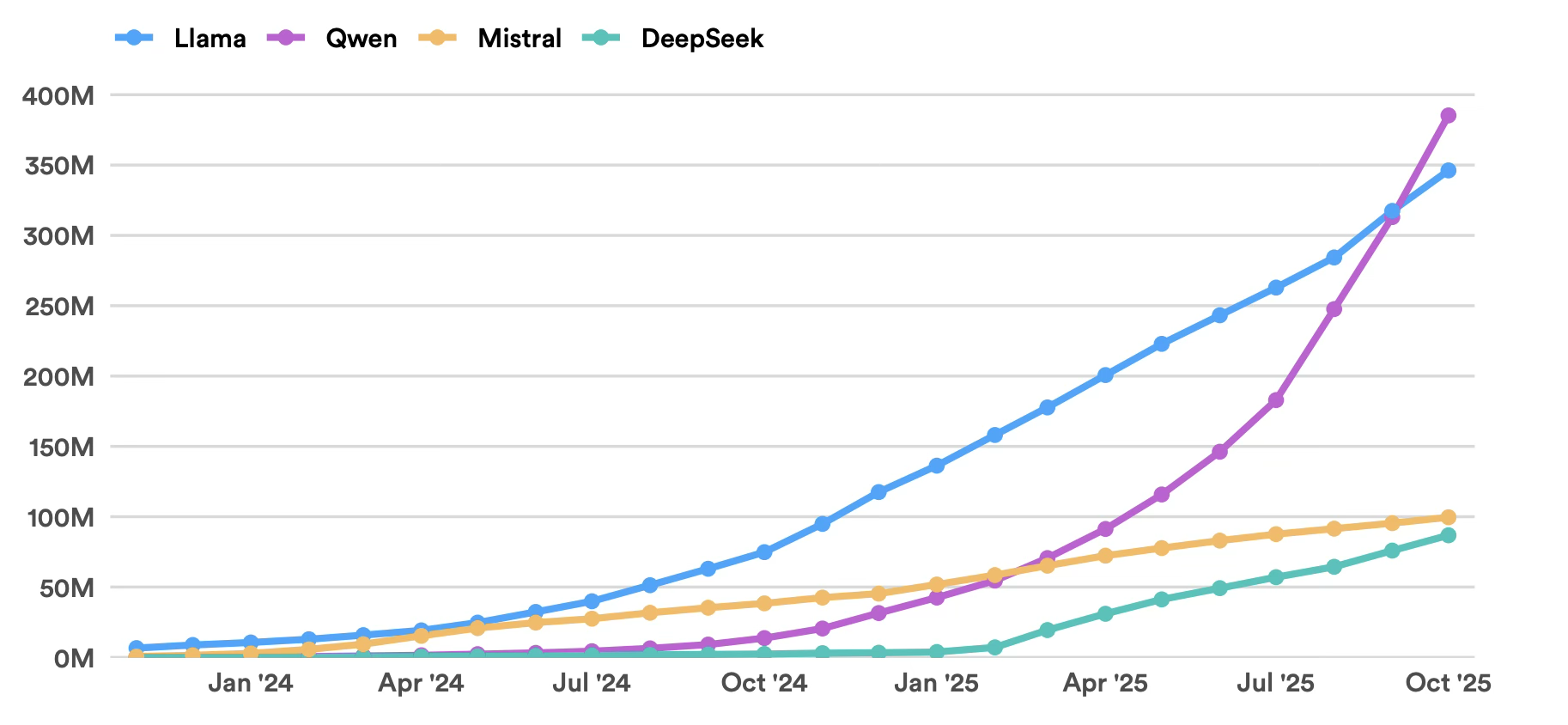

According to a December study by a16z and OpenRouter, Chinese open-source models now underpin nearly 30 per cent of total global AI usage. Between August 2024 and August 2025, Chinese developers captured 17.1 per cent of all Hugging Face downloads, surpassing their US counterparts (15.8 per cent). Furthermore, data from Stanford’s Human-Centred Artificial Intelligence (HAI) indicates that since January 2025, derivative models based on Alibaba’s Qwen and DeepSeek have outpaced those built on major western foundations.

Cumulative downloads of major open-source LLMs on Hugging Face from Nov 2023 to Oct 2025 [Stanford University]

The migration toward Chinese infrastructure is fuelled by two reinforcing factors: radical cost reduction through engineering innovation, and the Global South’s growing demand for data residency.

The Economics of AI Democratisation

The rapid ascent of models like DeepSeek and Qwen is largely a function of resource constraint. Denied access to the most advanced Nvidia silicon, Chinese labs were forced to innovate at the architectural level.

The economic implications are stark. DeepSeek’s V3/R1 model launched with pricing at $0.55 per million input tokens and $2.19 per million output tokens - a 90 to 95 per cent discount compared to OpenAI’s GPT-4o at launch. This pricing floor eventually collapsed further, with the R1 model becoming effectively free for many users.

While OpenAI reportedly invested over $100 million training GPT-4 on clusters of approximately 25,000 A100 GPUs, DeepSeek trained its V3 model for just $5.6 million using just 2,048 older-generation Nvidia H800 GPUs.

The technical driver is the innovative use of mixture-of-experts (MoE) architectures and sparse attention mechanisms. By activating the neural pathways relevant to a specific query - routing a calculus problem to a "math expert" node rather than engaging the entire model - these systems achieve frontier-level performance with significantly lower computational overhead.

For developing economies, this efficiency is transformative. A study by Greenspector found that DeepSeek discharges smartphone batteries 67 per cent more slowly than comparable proprietary models. In markets plagued by unstable power grids and reliant on older hardware, this efficiency metric is often the deciding factor in deployment.

Digital Sovereignty as a Service

Beyond economics, the proliferation of Chinese open-source models addresses a critical anxiety for the Global South: data sovereignty.

Reliance on US-based proprietary models (such as those from OpenAI or Anthropic) necessitates distinct vulnerabilities: data often must cross borders for inference, and access is subject to US foreign policy, including export controls and sanctions. OpenAI’s GPT-4, for example, is not offered in more than 20 countries due to company-imposed access restrictions shaped by US regulatory and geopolitical constraints. For a government in Indonesia or a financial institution in South Africa, building critical infrastructure on a strictly API-gated American service introduces unacceptable geopolitical risk.

Chinese open-source models offer an alternative: full localisation. The model weights can be downloaded and run on domestic servers in Jakarta or Nairobi. Once downloaded, access is irrevocable; the developer cannot remotely disable the system.

This fulfills the economic definition of a public good: it is non-rivalrous (usage by a Brazilian university does not diminish utility for a Thai startup) and, once released, non-excludable. Furthermore, the open nature of the code allows security researchers to inspect the mathematics for backdoors—a transparency mechanism that, ironically, provides higher assurance than the "black box" assurances of closed US systems.

Indigenous Innovation

The utility of this approach is already manifesting in indigenous applications across the emerging world. On October 11, Uganda launched "Sunflower," an LLM built on Alibaba’s Qwen architecture local language translation and content generation. Designed to bridge the digital divide, it allows farmers to receive agricultural advice in Luganda and students to translate educational materials into Runyoro.

"The goal is a mother in Mbarara asking health questions in her dialect and receiving accurate guidance," noted Dr. Zawedde, a lead on the project. With Qwen 3 supporting 119 languages - including under-represented Javanese, Cebuano, and Haitian Creole - these models are servicing the country’s 46 million population (who speaks over 50 languages) frequently marginalised by Western, English-centric training data.

As the country’s ministry of ICT and national guidance said, the system renders “technology more accessible to every citizen regardless of language or location.

Similarly, Malaysia has deployed NurAI, positioned as the world’s first Sharīʿah-aligned LLM. Utilising DeepSeek’s foundation and refined by the ASEAN-China AI Lab, supports Bahasa Melayu, Bahasa Indonesia, Arabic, and English. The initial rollout targets a market of 340 million people across Malaysia, Indonesia, and Brunei, ensuring output complies with local cultural and religious standards.

The democratisation of AI via Chinese code challenges the prevailing narrative of US technological supremacy. While the US retains a stranglehold on the means of production (semiconductors and fabrication equipment), China is successfully capturing the means of development.

By releasing efficient, permissive, and capable models, Chinese firms have engineered a product that thrives in the resource-constrained realities of the Global South. This alignment is lowering the entry barrier to AI development globally.

The next generation of AI applications in the developing world is being built on Chinese foundations, not because of geopolitical allegiance, but because the code is accessible, affordable, and - crucially - sovereign.

(Editor: wangsu )